In an era dominated by speed, visibility and relentless novelty, Beast’s latest body of work moves in the opposite direction. His series “…and we hired a bloke to fix the wall” unfolds slowly, discreetly, and far from the centres of attention. Installed on abandoned walls in uninhabited historical towns, the works do not announce themselves. They wait. Beast, an Italian street artist active since 2009, has produced more than 200 urban installations across Europe, the United States and Japan. His early practice was rooted in political satire: gold-framed mash-ups depicting contemporary figures of power, placed directly onto the street with an unmistakable critical edge. Over time, both the scale and the ambition of his work expanded. Large-format paste-ups began to replace advertising posters; murals occupied the facades of abandoned buildings. What remained constant was his commitment to the street as a space of direct encounter. In recent years, however, the focus has shifted decisively. Rather than addressing the immediacy of political events, Beast has turned his attention to memory, history and the physical traces of time.

Walls as witnesses

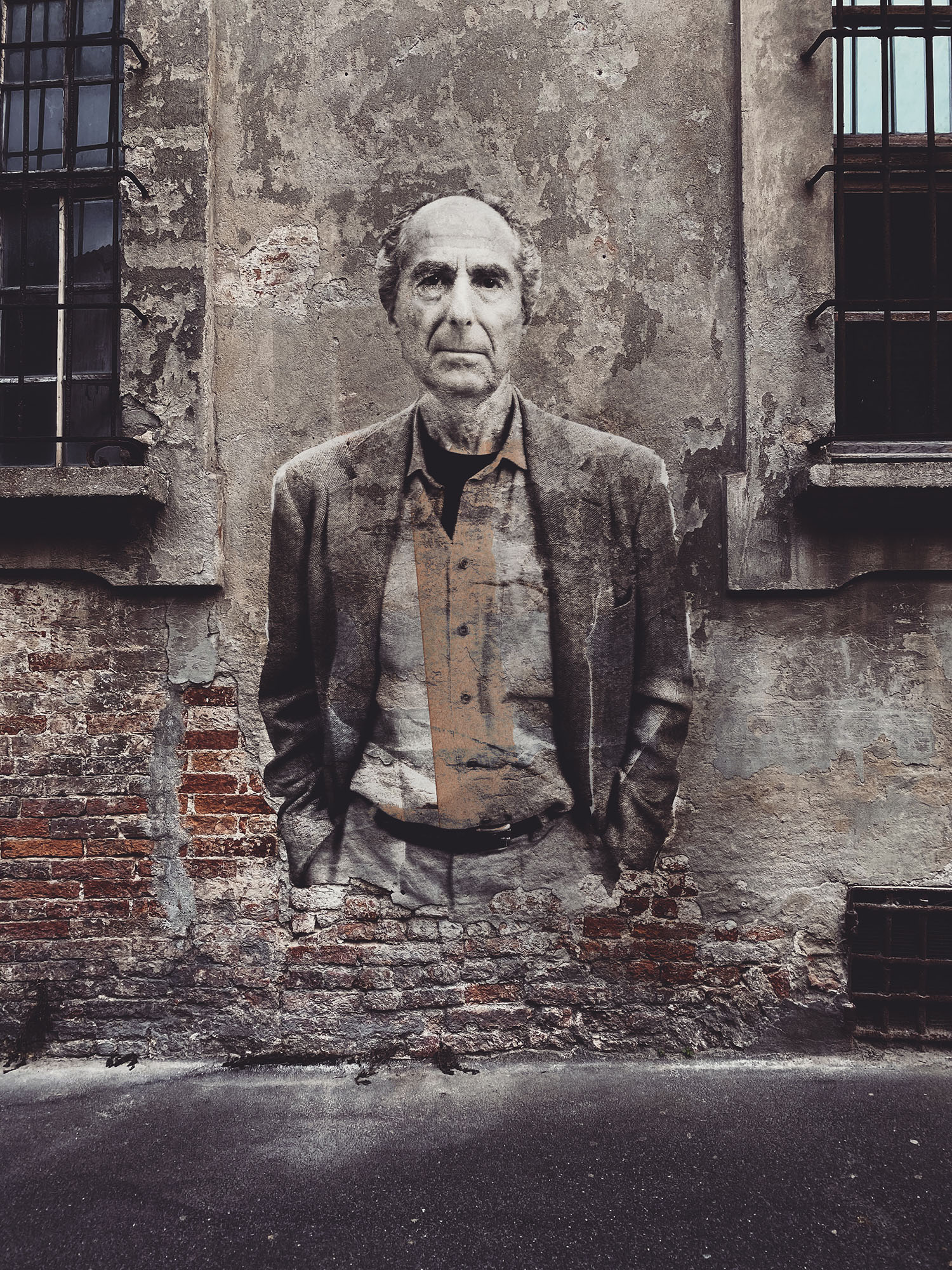

At the heart of “…and we hired a bloke to fix the wall” lies a simple but rigorous method. Each work begins with the wall itself. Beast carefully photographs the chosen surface, documenting its cracks, stains and signs of erosion. That image is then digitally overlaid onto the portrait of a historical figure. The texture of the wall becomes part of the subject before the artwork ever returns to the street. Once printed, the paste-up is installed on the same wall that generated its surface. When executed correctly, the alignment is exact: fractures continue seamlessly from masonry to paper, creating the impression that the figure is emerging from within the wall rather than being applied to it. The result is subtle and disconcerting. The image does not impose itself; it appears to surface. This technical precision is not an aesthetic flourish but a conceptual necessity. The wall is not a backdrop. It is an active element of the work, embodying the passage of time and the process of forgetting.

Figures that endure

The individuals portrayed in the series come from different disciplines: writers, artists, philosophers and thinkers such as Philip Roth, John Updike, Carl Gustav Jung, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Jackson Pollock, Francis Bacon, Jasper Johns, Ernest Hemingway, Simone de Beauvoir and Eduardo De Filippo. What connects them is not style or ideology, but endurance. Their ideas have survived the contexts that produced them. Positioned on decaying walls, these figures generate a dialogue between physical deterioration and intellectual persistence. The material surface crumbles; the thought remains. Importantly, these are not celebratory portraits. Beast avoids monumentality. The figures appear fragile, provisional, exposed to the same forces of weather and removal as the walls that host them. They are present, but not secure.

The irony of repair

The title of the series plays a crucial role in framing the work. “…and we hired a bloke to fix the wall” carries an understated, distinctly British irony. It suggests a practical solution, a modest intervention, the kind of phrase one might use to dismiss a problem rather than confront it. This irony stands in deliberate contrast to the seriousness of the subject matter. The series deals with memory, historical awareness and cultural erosion, yet its title evokes the impulse to repair, conceal or smooth over damage. The suggestion that a wall—and by extension, history—can simply be fixed is quietly undermined by the works themselves. Rather than covering the cracks, Beast exposes them.

History as defence

A key reference for the series is a statement by historian Howard Zinn: “If you don’t know history it is as if you were born yesterday. And if you were born yesterday, anybody up there in a position of power can tell you anything, and you have no way of checking up on it.”

This sentiment underpins the project. “…and we hired a bloke to fix the wall” is not an exercise in nostalgia, but an assertion of historical awareness as a form of vigilance. Forgetting, Beast suggests, is not neutral. It creates vulnerability. By allowing historical figures to re-emerge from neglected surfaces, the works act as reminders rather than explanations. They do not instruct the viewer, nor do they offer resolution. They simply insist on presence.

The choice of place

The decision to work in abandoned historical centres is central to the series. These locations are free from the pressures of visibility and consumption. There is no curated audience, no institutional framing. Encountering the work is often accidental. In such settings, the artwork does not compete with advertising or spectacle. It exists within an already layered environment, adding to a narrative that predates it. The wall’s history remains legible, and the image becomes part of that continuity rather than an interruption imposed from outside.

Street as exposure

Beast has long described the street as an open-air gallery, but not in an idealised sense. Public space offers no protection. Works are subject to weather, indifference, vandalism and removal. This exposure is fundamental to the meaning of the series. Like memory, the works are temporary. Their disappearance is not a failure but an extension of the concept. What matters is the encounter, however brief.

Reading the cracks

Ultimately, “…and we hired a bloke to fix the wall” is less about restoration than attention. It questions the instinct to repair without reflection, to erase signs of age in the name of progress. The damaged wall becomes a site of meaning rather than a problem to be solved. Beast does not propose solutions. He presents surfaces that demand to be read. In doing so, he quietly asserts that some cracks are not flaws to be corrected, but traces worth preserving.