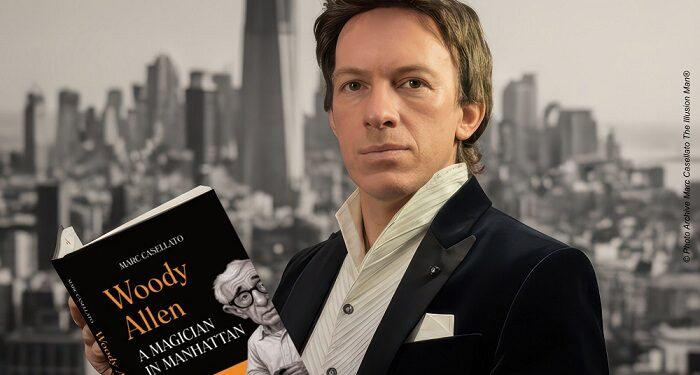

What connects Woody Allen, Georges Méliès, and Harry Houdini? According to Italian illusionist and author Marc Casellato, the answer is simple: illusion itself.

Casellato’s new book, Woody Allen: A Magician in Manhattan, celebrates the legendary director’s 90th birthday by looking at his career through the lens of magic — not just as spectacle, but as a way of understanding storytelling, deception, and belief.

The idea for the book, Casellato says, grew out of a lifelong fascination with both cinema and conjuring. “Magic deceives only to give back wonder — and Woody Allen understood this better than anyone,” he explains.

Casellato’s journey began with a curiosity about how many of Allen’s films, even the comedies, contain elements of illusion: hypnotists, clairvoyants, magicians, and dream sequences that blur fantasy and truth. Sleeper, Zelig, The Purple Rose of Cairo, Shadows and Fog, Scoop, and Magic in the Moonlight — all feature characters trapped between what they believe and what they can prove.

“Woody Allen’s cinema,” Marc writes, “functions like a magician’s routine. There’s setup, misdirection, and revelation. The joke is never just for laughs — it’s a trick about perception.”

Casellato, who has performed internationally as an illusionist and magic historian, writes with the insight of someone who understands the choreography of deception. He traces the origins of Allen’s fascination with magic back to the filmmaker’s youth in 1940s New York, when a small box of magic tricks and a book sparked a lifelong interest in illusion.

The book connects Allen’s worldview to that of the great illusionists of history. “Moving pictures themselves are born from a trick,” Casellato notes. “The persistence of vision makes still frames appear alive. In that sense, every filmmaker is a magician — and Allen is one who never stopped believing in wonder.”

In Woody Allen: A Magician in Manhattan, Casellato also expands the conversation beyond Allen, drawing parallels to other artists who turned illusion into cinema: Orson Welles, who blended magic and storytelling; Ingmar Bergman, who used the language of dreams; and Georges Méliès, the stage conjurer turned pioneer of special effects.

The result is an engrossing hybrid — part film essay, part cultural history, part meditation on creativity. Casellato moves fluidly from Houdini’s escapology to The Irrational Man, arguing that both magician and filmmaker work toward the same goal: to make audiences feel the thrill of believing in the impossible.

Elegant, witty, and deeply personal, Woody Allen: A Magician in Manhattan transforms critical analysis into a love letter to imagination itself. “What connects Woody Allen to Houdini,” Casellato concludes, “isn’t the trick — it’s the need to astonish, to remind us that reality is never as solid as it seems.”

The English edition follows the Italian version, Woody Allen: Un Mago a Manhattan, which was selected for the 37th Turin International Book Fair’s Independent Authors section. The book is now available worldwide in hardcover and paperback via Amazon.